The following is an interview with Christian Bök who achieved the extraordinary task of implanting a pair of love poems in the genome of a deathless bacterium, Deinococcus radiodurans which glows red upon reading, writing, and replicating the poem in its DNA. After 25 years, Bök has completed The Xenotext, the title of this project which confounds the barriers between genetics, poetry, code, art, myth, astrophysics, and deep time. Any poem that outlives its creator must carry with it a deeper sense of connection with the past, looking forward to the future, all with a humbling awareness that we cannot do our work alone. While authored by Bök, the work did not reach its completion without the unsummable expression of love and empathy from others. This conversation with Elisabeth Sweet scratches the surface of the work, the vision, and the value of perseverance and connection against cosmic odds.

D. radiodurans fluorescing with mCherry, the segment of genomic mutation which evokes the rosy glow of the poems’ dialogue. Courtesy of the artist.

Elisabeth Sweet: The Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice remains central to The Xenotext. Different versions of the story have persisted over time, so can you please recount the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in your own words very briefly?

Christian Bök: Mourning the demise of the nymphet Eurydice (killed by a viper), the herdboy Orpheus descends into the Underworld, striving to rescue her from the kingdom of Death, all the while using his songs to quell the dangers en route. And while leading her home, he suffers doubt that she follows him across the threshold into Life, and because he looks back, he loses her forever, squandering his chance at salvation. The sorrow of Orpheus (after this forfeiture) so offends the witches of Dionysus that they dismember him during their bacchanals. The story perhaps provides an allegory about the failure of poetry to bring the dead back to life, suggesting that poetry can serve only as inadequate expression of grief in the face of such a failure.

E: You cite William S. Burroughs’ famous aphorism, “Language is a virus from outer space” in the book, and theVERSEverse has lifted this aphorism for the title of the exhibition. What can you tell us about the influence of this line by Burroughs, or perhaps his work more broadly, upon the overall concept of The Xenotext?

C: William S. Burroughs provides a paranoid statement about language, suggesting that it might, in fact, be something ‘alien,’ a viroidal parasite that has colonized our brains, transforming them into organs for its own reproduction, evolving for its own sake, with instincts separated from the interests of its ‘host.’ The Xenotext has, likewise, hijacked the biogenetic mechanisms of a deathless bacterium, implanting a package of ‘alien words’ into the genome of a life-form so that it becomes not only a durable archive for storing a poem, but also an operant machine for writing a poem in response — a poem that can literally survive forever. I have, in effect, created a work of ‘living poetry,’ whose words can literally reprogram the behaviour of living things.

E: Has your perception of The Xenotext changed with the reception of the works created for the Special Edition by your peers, nine of whom we are celebrating in this exhibition?

C: The Xenotext probably transcends my own attitudes about it, since the work now has a ‘life of its own’ (so to speak) — and I can never predict how a work might find its audience in the world. I think that, given the heroism of this project in the face of the vast odds against its fulfilment, I might have created a canonically significant work of art (one that has the capacity to inspire the ambitions of other poets), and I feel gratified to know that peers have taken inspiration from my perseverance. A work of art might depend upon its own viroidal capacity to ‘influence’ the minds of others, causing them to add value to the work by commemorating it — and I like to think that the nine contributors to this exhibition might help to make the work even more ‘infectious.’

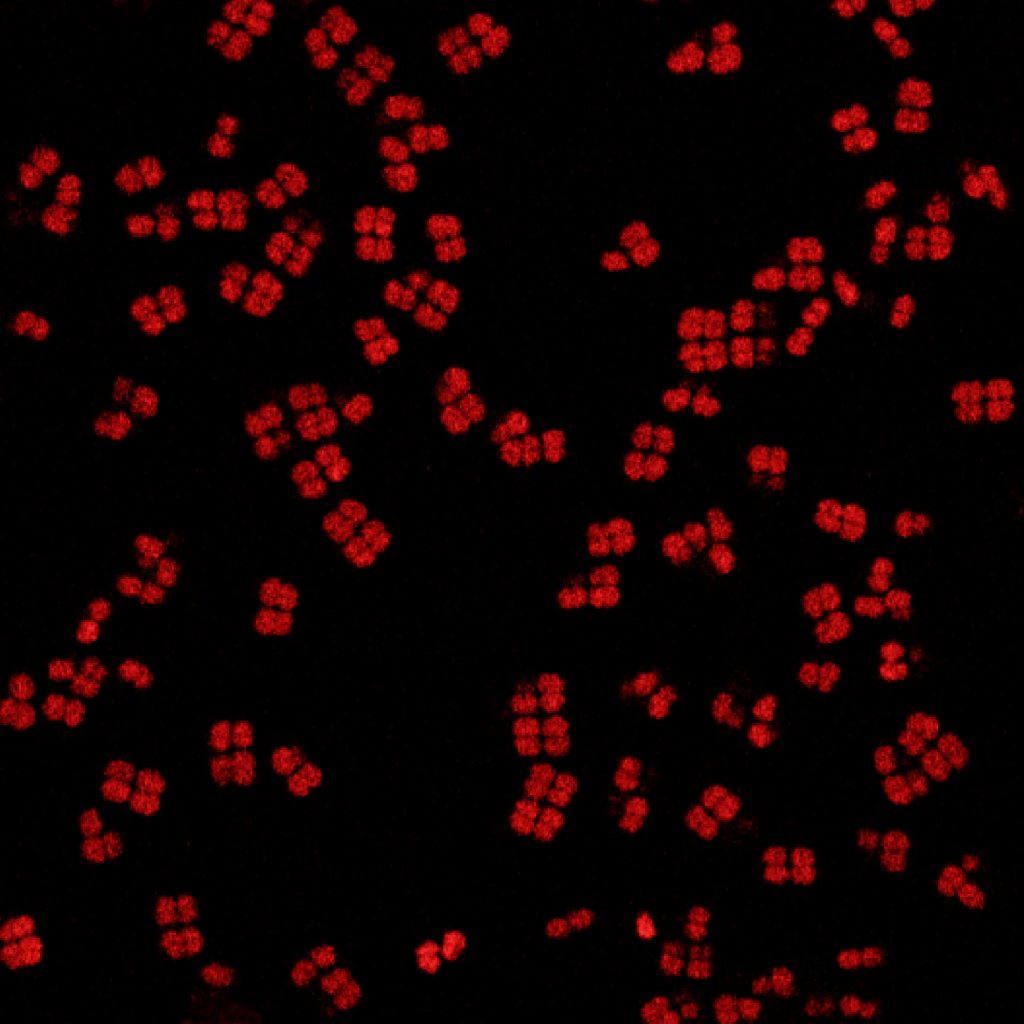

‘The Fay Imp in All Living Things’ depicts a colony of D. radiodurans, fluorescing with a ‘rosy glow’ under the influence of ‘The Xenotext.’ Courtesy of the artist.

E: With The Xenotext, you have effectively implanted a virus (language) into a bacterium (D. radiodurans), which does not easily evolve, because it resists mutation, repairing damage to its own DNA very rapidly. But with your chromosomal implantation, the behaviour of the bacterium changes, responding to the poetry by emitting a rosy glow. So I wonder: could this poem be a forcing function for the bacteria’s evolution?

C: You have asked a very incisive question. I have chosen D. radiodurans as the ‘host’ for my poem, in part, because the ability of the germ to repair its own DNA makes the germ a durable archive. I have designed a viable, benign protein that might persist long enough in the cell for the poem to remain both detectable and isolatable, before the cell metabolizes it. I do not yet know if this protein offers any ‘benefit’ to the survival of the organism (albeit such a benefit seems unlikely) — and in any case, drift in the replication of the gene can degrade the integrity of the poem over time (perhaps causing the germ to evolve back to its ‘normal,’ wilder state); nevertheless, this process is likely to be very slow, given these biogenetic mechanisms of repair.

E: How does The Xenotext engage with the generative dimension of genetics?

C: The Xenotext resembles an algorithm (written according to a set of restrictive constraints, all of which allow the poem not only to survive in a living microbe, but also to produce a viable protein). The poem becomes what it says that it does. When the organism generates the protein that enciphers a text, whose first lines say: ‘The faery is rosy/ of glow’ — the organism glows in response, fluorescing rubescently, like the ‘faery’ described in the poem itself. The work establishes a dialogue between the genetic code and an English text – and the sheer scale of the strictures upon such a dialogue might make this work one of the most stringently constrained poems ever written. A gene is, in effect, a kind of poem that makes life live.

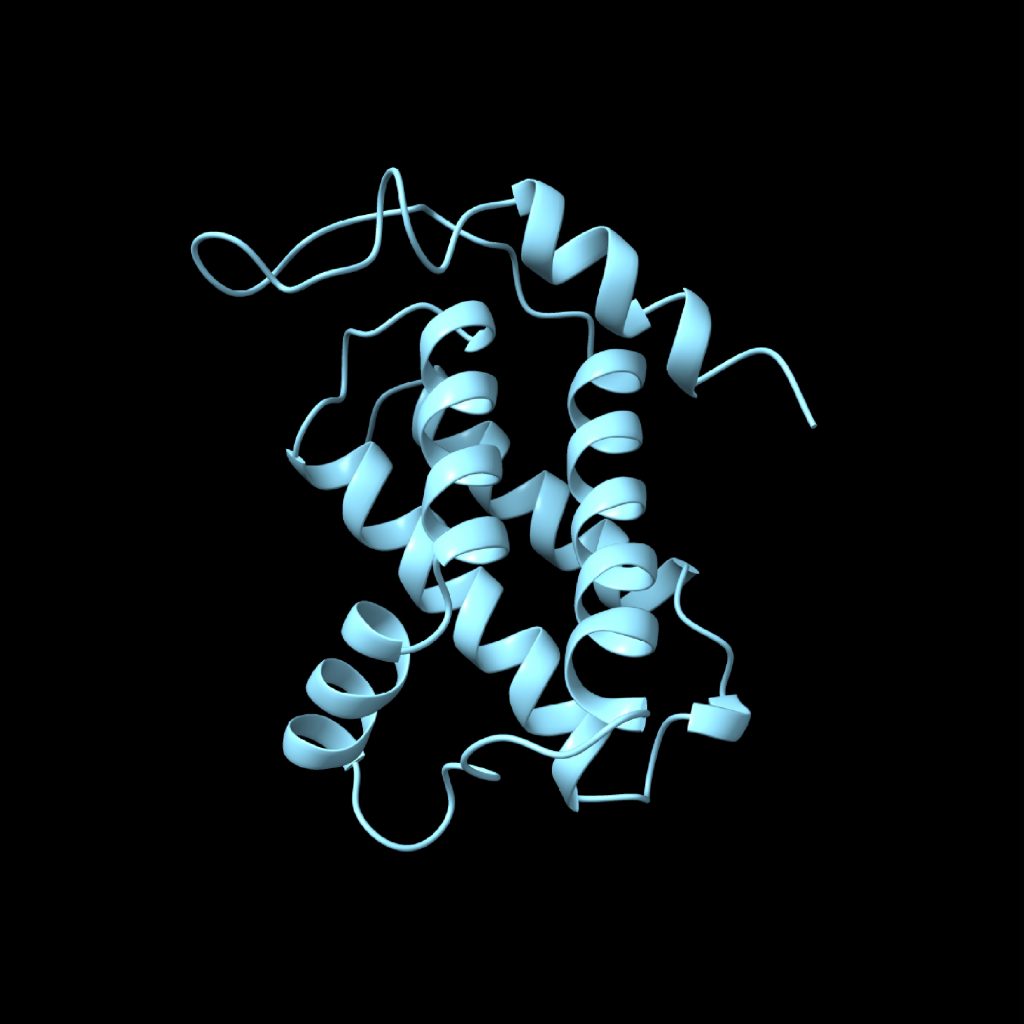

‘Protein 13’ depicts the pliant ribbon for the sequence of 140 amino acids that encode the poem ‘Eurydice’ from ‘The Xenotext.’ Courtesy of the artist.

E: In the book, you write that there exist 7,905,853,580,625 encipherments of the English alphabet, from which you might have derived The Xenotext (and almost all of these ciphers result in absolute nonsense). You have, in fact, found the only encipherment that can make a pair of eloquent poems. Are you the progenitor or the discoverer of them?

C: The Xenotext partakes of some spookiness. The chances of these two poems arising from the constraint fall within the range of one in eight trillion — odds that might rival the chance of any planets hosting life, like ours, among the billions of stars in the galaxy. As far as we can tell, only our planet among the trillions of likely worlds seems to harbour any poetry at all — and for this reason my two poems provide an allegory for the anomaly of such an occurrence, replicating the cosmic rarity of life itself. I might note that the odds of finding a protein that can encode the second sonnet remain even more colossally improbable. I have not written these poems so much as I have derived them, finding them, hidden with the rules that govern our biochemistry.

E: We have discussed how the Earth might be either a lone culture left to itself in the cosmos or a late culture among many potentially adversarial civilizations, stealthy and watchful. A host of questions about readership and the relevance of poetry written by humanity arise in these speculations — and since The Xenotext addresses the role that poetry might play in the deep time of the cosmos, what becomes of the reader? Does a poem simply need to exist to matter, or must it be read and by whom?

C: The Xenotext takes some of its inspiration from Voyager 1 — the space probe that has left the imperium of the Sun, bearing a golden record that features an anthology of sounds and images from the heritage of our species. I regard this object as the most important of all artifacts ever made by us — and yet its contents might go unread for the lifetime of the universe. I believe that, if a poem needs a reader to matter, then every poem must, perforce, already matter, because every poem has at least one reader — i.e. the writer, appraising the work after completing it. I think that, in the case of The Xenotext, I aspire to have a ‘thinkership,’ in which no one needs to read my work — but everyone must, nevertheless, admit to its significance.

E: How do you think “beings” in the future might decode and then peruse The Xenotext?

C: The Xenotext might resemble a sphinx carved from a black block of granite in the desert, like a cenotaph bedecked with hieroglyphs that no one can understand — and yet, even though no readers might decode these messages, the craftsmanship of the work testifies to the intelligence of the maker. The future aliens who might listen to the golden record on Voyager 1 are going to learn much about us without ever having to ‘understand’ what we say. I think that I have left a lot of evidence in the genome of D. radiodurans to testify to the ‘artificiality’ of the organism — and if any hierophants of the future discover it, the fact that such a monument even exists at such a small scale already says much about the mind that has preceded their minds.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Visit the exhibition The Xenotext: “language is a virus” on objkt

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Christian Bök is the author of ‘Eunoia’ (2001), a bestselling work of experimental literature, which has won the Griffin Prize for Poetic Excellence. After 25 years of effort, Bök has completed ‘The Xenotext’ — a project that requires him to encipher a poem into the genome of a bacterium capable of surviving in any inhospitable environment. Bök is a Fellow in the Royal Society of Canada, and he teaches at Leeds Beckett University.

Elisabeth Sweet is a poet exploring patterns of randomness. Her practice infuses ritual with critique on contemporary society, namely the forfeiture of attention in return for convenience. She leads communications and production at theVERSEverse, a digital poetry gallery where poem = work of art. Elisabeth’s poetry has been exhibited in London, New York City, and Paris, with a solo show in Berlin. She publishes weekly writings to her Substack, Species of Value.